In a world where the concept of identity often revolves around tangible factors such as appearance and career, personality tests provide a breath of fresh air for people looking to define themselves in their character, rather than in statistics. However, with a dimension that exceeds the physical world, how can one be sure that personality tests are helpful, or even accurate? Unfortunately, most personality tests hinge upon psychologically tricking the test-taker into believing they are being evaluated correctly. A quintessential example: the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator, or MBTI test, which misleads its users to believe that they are experiencing self-enlightenment through flattery, false promises, and pseudoscientific beliefs. The test’s formulaic structure and grand proclamations cause more harm than good because they lure individuals into trusting the guidance of a contrived test over their own autonomy.

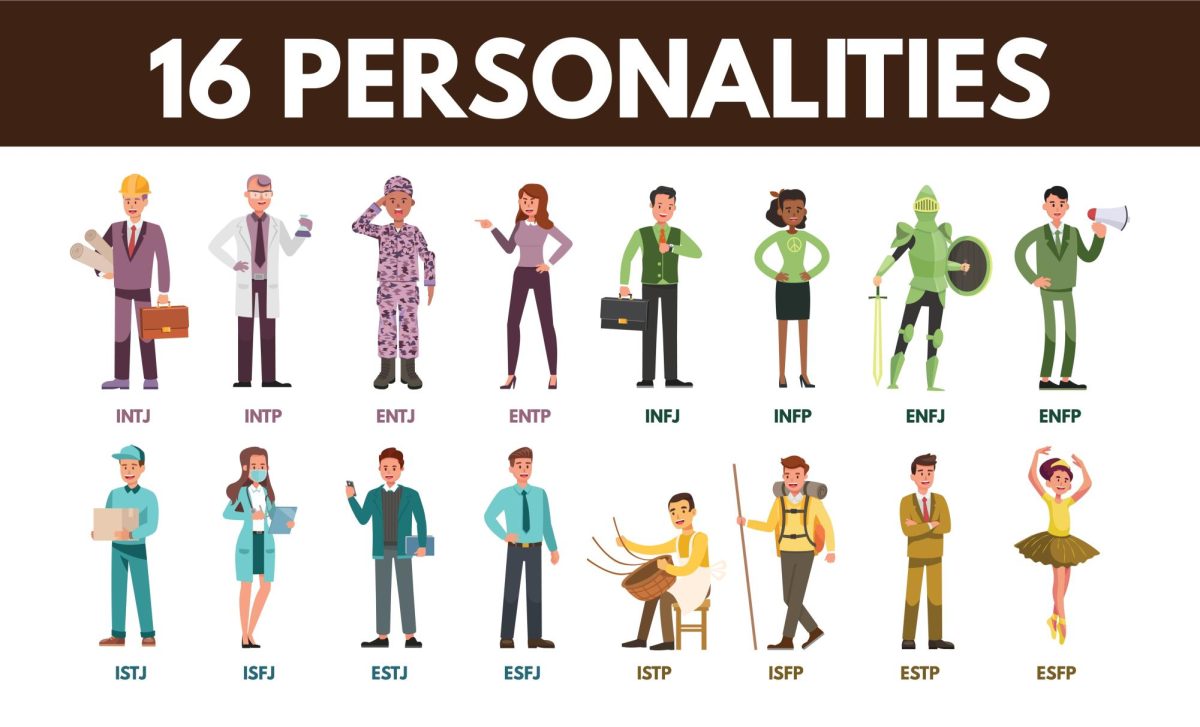

The fallacy of the MBTI test is stated directly in the title of the website that houses it: “16personalities”, denoting the sixteen—and only sixteen—personality groups that a test-taker may fall into. Immediately, the test insinuates that somehow, it can categorize eight billion people on Earth into sixteen distinct boxes. The test-taker’s MBTI type consists of four letters which supposedly represent four aspects of their identity. For each letter, there are two options, one of which applies to the user. Extroverted or introverted, intuitive or observant, thinking or feeling, and judging or perceiving. By designing two polar categories for the test-taker, the Myers-Briggs test suggests that there are only two boxes that an individual can fit into (e.g. only extroverted, or only introverted). While the test results include percentages of each characteristic to suggest that there are no absolutes, the binary-like structure of the examination still lacks the nuance of reality.

Okay, sure—the MBTI lacks subtleties in its evaluation, but it must still offer an accurate description of an individual’s basic attributes, right? Unfortunately according to the American Psychological Association, like most personality exams, the test relies on a psychological phenomenon known as the “Barnum effect”, or “the tendency to believe vague predictions or general personality descriptions” especially when those descriptions are flattering. Named after circus showman P.T. Barnum, the Barnum effect can be spotted immediately by browsing through the 16personalities website. With sweeping phrases like “charismatic and inspiring”, “bold, imaginative, and strong-willed”, “smart and curious”, and more, Myers and Briggs ensure that their self-proclaimed “freakishly accurate” test finds some way to appeal to the test-taker while hiding the fact that they have little insight to provide. Moreover, with a prominent display of celebrities and fictional protagonists that have been arbitrarily assigned the same MBTI type, test-takers are distracted from the lack of substance on the rest of the page. With the test boasting that over 90% of past test-takers have found their evaluation to be either accurate or very accurate, it’s clear that the Barnum effect is working.

Fortunately, most people take the tests for mild amusement rather than a rigorous evaluation of their psyche. MBTI should be an innocuous way for people to have fun in their leisure. However, research has shown that the test has a surprisingly growing and profound impact in the professional world. In an NPR interview with Merve Emre, an associate professor at Oxford University and author of The Personality Brokers: The Strange History of Myers-Briggs and the Birth of Personality Testing, the original creators in 1950 believed that they would be able to “design a questionnaire that would help fit people to the jobs that were best suited for them.” Instead, the test first gained popularity among corporations looking to employ a specific type of person rather than individuals searching for career help. Today, several Fortune 500 companies and even the CIA allegedly utilise the MBTI test as part of their hiring process. However, as Emre points out, corporations mislead their workers or prospective employees into believing that they’re aiding them on a journey of self-discovery when they’re actually relying on pseudoscience to encourage workers to “bind themselves freely and gladly to the work that they do… as well as [turn] profits for the corporation.”

But corporations cannot absorb all the blame. The MBTI test blatantly misadvertises itself as a tool that will make the test-taker feel “incredible to be finally understood.” In the results portion of the website, test-takers are offered advice ranging from tips on productivity to instructions for a stable marriage. And for an additional thirty dollars, the test claims that it can provide users a guide to “cultivate deep self-improvement”, “improved relationships”, and “an advanced career”, essentially promising people everything short of a million dollars. The main issue with the test is that it takes itself too seriously, and asks everyone else to do the same. Even at its conception, the test pictured itself as instrumental in the path to enlightenment. When discussing the test, Katharine Briggs, the deeply religious cofounder of the Myers-Briggs test asserted that “the only way to really save your soul was to figure out who you were [through the test].”

Surprisingly, there have been claims that the test has some positive emotional benefits. In a study published on Frontiers in Psychology titled, “Personality assessment usage and mental health among Chinese adolescents: A sequential mediation model of the Barnum effect and ego identity”, researchers Jie Hua and Yi-Xin Zhou from Nanjing University discovered that “the personality feedback provided by the MBTI is somewhat vague and general, which motivates the Barnum effect among users. The Barnum effect then sequentially enhances the adolescent ego identity, elevates their sense of subjective well-being, and reduces the levels of depression and anxiety”. In other words, the test relies solely on a psychological placebo to convince user’s that they are being properly and positively evaluated. Thus, the cons continue to outweigh the pros on this matter, because by placing trust in a personality test like MBTI, people also lose a part of their own autonomy. They trust that a formulated exam knows themselves better than themselves and can make better decisions than them, but why?

Sadly, true self-discovery can be a painful and arduous journey. Examining one’s own psyche, which is inevitably riddled with as many flaws as strengths, can be discouraging. It’s much easier to place faith in something that feeds comforting thoughts and pleasant ideals, but let’s remember that it’s only a website designed to satisfy you, trick you, and extract money from you, all without actually helping you understand yourself. Hence, it’s important to be cognizant of the nuance and inaccuracies behind the MBTI and other personality tests. Don’t take them too seriously, enlightenment never comes so easily.